Many people (and sociologists!) have noticed that, when you ask someone to rate themselves on a scale of 1 to 10, they give themselves a 7 typically. It doesn't matter what it is. For example, if you ask someone to rate how well they drive, they'll say 7. I've been in interviews where candidates are asked to evaluate their SQL skills, for instance, on a scale from 1 to 10. Their answer? "I'm about a 7."

Many people (and sociologists!) have noticed that, when you ask someone to rate themselves on a scale of 1 to 10, they give themselves a 7 typically. It doesn't matter what it is. For example, if you ask someone to rate how well they drive, they'll say 7. I've been in interviews where candidates are asked to evaluate their SQL skills, for instance, on a scale from 1 to 10. Their answer? "I'm about a 7."If everyone says they're a 7, one inference to make is that people are not objective when it comes to things close to them, like their children or their own skills. This is sometimes called the 'Lake Wobegon Effect', named after Garrison Keillor's fictional hometown in which 'all children are above average'. You can't trust people to rate themselves, it is inferred. That's why driver's tests, SATs, and other methods of evaluation were invented.

But another, often-overlooked inference is that people value different things differently. You might value driving fast, while I might value driving safely, or in a way that shows off my car, or in a way that is fuel efficient, or in a way that doesn't remind me of a terrible accident I once had. Since driving can be many things to many people, they answer in terms of what driving means to them when asked abstract questions like, "How good are you at driving?" The reason people are a 7 at SQL is that they know enough to be able to do their jobs, but they could always learn more. There is no absolute standard of SQL-ness that they could rate themselves against. They're a 7 at writing reports, performance tuning, deploying code, or whatever else their (previous) job entails.

| 9 for fight scenes; 2 for plot |

The realization that people value different things differently is also important in everyday life. We'd have a lot fewer arguments about whether or not someone is a good driver, teacher, or cook, or whether or not something is a good movie. Or, at the very least, we'd have more concrete arguments.

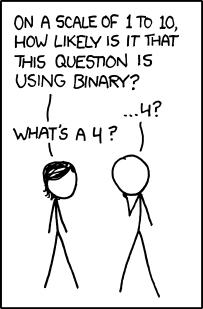

And, maybe sociologists would ask us less bizarre questions.

No comments:

Post a Comment